Yao-Chinese Folktales thrilled the audience in its Bilibili run, but the journey to compete with the West is long and arduous.

A screenshot of Nobody, episode 1 of Yao-Chinese Folktales. Photo from CFP

By HU Yujing

Since its New Year’s Day premiere, animation series Yao-Chinese folktales has been a massive hit in China, thanks to its mythology and production values. Characters such as the wild boar and Prince Fox are loved by audiences, which has brought unprecedented merchandise sales. Director CHEN Liaoyu has already confirmed that a second season will be produced.

The finale, Fly Me to the Earth, was aired on February 12, ending the first season run of the coproduction by Shanghai Animation and Bilibili, a Chinese YouTube competitor. The eight standalone episodes were each directed by different teams under the guidance of Chen.

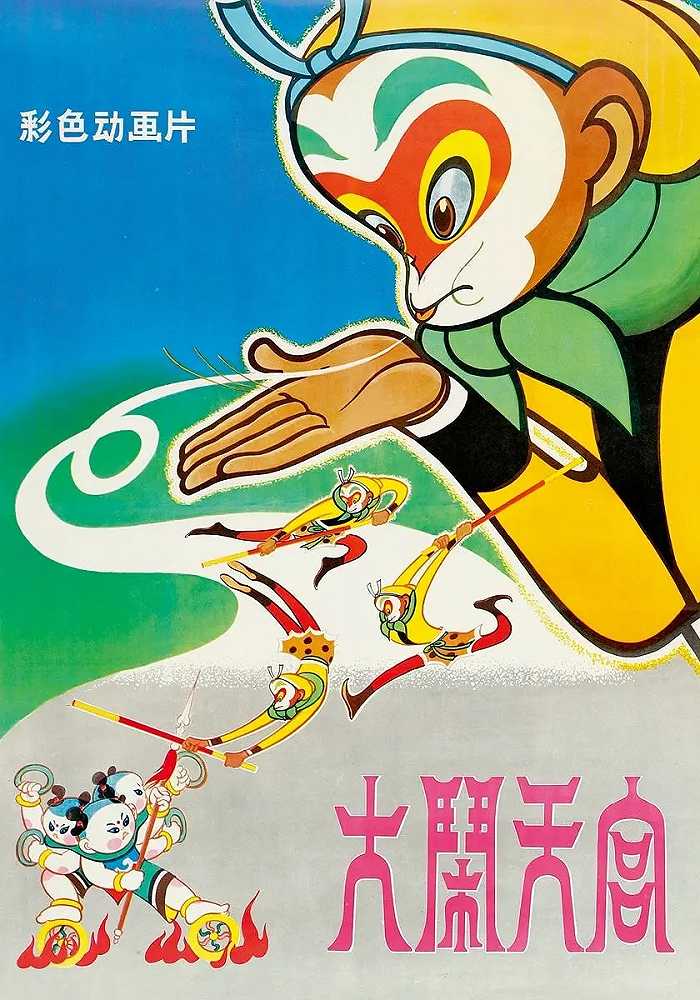

Animation never lost its appeal in China and this year is the centenary of Chinese animation. Time-honored Shanghai Animation Film Studio is celebrating event with Yao-Chinese Folktales.

“Every creator can interpret the Qitan (Chinese folklore) stories in their own ways. After all, folklore is the product of imagination, the projection of inner desires, or the presentation of human nature.”

The team was able to incorporate almost all contemporary animation genres, including papercut art Ship Down the Well, computer-generated (CG) 3D She Wolf, stop motion Fly Me to the Earth, CG and hand-painting Old Man Yang, cel shading Null Island, and 2D hand-painting in The village bus took away Wang Haier and the Gods.

Chen wanted the directors in their 30s, experienced, prolific and eager to try new things. He also preferred those he knew personally. Some were his students, others were internet acquaintances.

GU Yang, co-director of the Old Man Yang, was Chen’s student at the Beijing Film Academy. LIU Maoning (The Village Bus Took Away Wang Haier and the Gods) failed the admission test for the academy’s animation school, but stayed late outside the exam room to meet Chen and showed him his rustic drawings, which were the root of the fourth episode.

Producer Bilibili came in at the halfway stage. Shanghai Animation was responsible for the content and production, while Bilibili provided funding and internet traffic.

Bilibili was also able to offer specific suggestions on how the short films work and how to make the storyline appeal to a wide audience. In the original ending of the story, Nobody was a wild boar beaten to death by Monkey King. But in Zhang’s version the Monkey King gives the boar a gift and tells him how to call for help when in distress.

CHANG Guangxi, director of Lotus Lantern (1999), offered help with scripts, storyboarding, and production. The 80-year-old director has been encouraging young directors to be more persevering, open-minded and daring. Shanghai Animation Film Studio has always been creative and forward-looking.

The opening episode Nobody went viral as soon as it was released. Based on the classis Journey to the West, the short film depicts the hard life of an ordinary worker with witty innuendos.

Nobody chosen as the first episode because it was the most mainstream. As expected, the second story Goose Mountain, an unintelligible pantomime with a voiceover, stirred a more diverse response, but the series continued to receive a high rating.

“I don’t understand, but amazing” was one of the most popular comments.

Bilibili also gave Yao-Chinese Folktales plenty of support by encouraging resident creators to make videos to make tribute material.

WANG Shuang, a producer of animation films, told Jiemian that the first two episodes were stunning. The series’ short length gives the directors more freedom and flexibility in topics, characters, and perspectives.

Chinese short animations have been performing nicely in international animation festivals, but the domestic market isn’t commercial enough.

Video streaming platforms could be the key to forming a commercial market. The audience wants more short content and short films are easier to make than feature films.

HUANG Shi of the school of animation and digital arts at the Communication University of China, attributes the success of Yao-Chinese Folktales to a great number of animators silently dedicating themselves to the industry for many years.

Chen and Shanghai Animation are now committed to a sequel and characters like the wild boar and the Prince Fox are likely to be developed into popular IP rights.

Yao-Chinese Folktales is to Bilibili what Love, Death & Robots is to Netflix, strengthening its position while infiltrating animation and anime. Love, Death & Robots did a lot for the Netflix brand. Bilibili Yao-Chinese Folktales can do the same.

Chen believes short film techniques, styles and narrations will nourish the development of feature films. But it’ll be no mean feat to transition to feature films from the commercial point of view. Profitability, it seems, always comes at the cost of artistic integrity, as witnessed in the handling of the ending of Nobody, the very first episode.

“But this dilemma may be addressed if we always respect the audience. They are straightforward in appreciating art and generous in recognizing the creators’ efforts,” said Chen.

Yao-Chinese Folktales ends with the eternal question of all children on journeys everywhere: “Are we there yet?”

Chen has the same question for Chinese animation: “We’ve embarked on the journey, but are we there yet?”