Coordinated conservation efforts, better public awareness, and most importantly, not discounting the environmental impact of hydroelectric projects will help restore habitat and protect other species.

Photo from CFP

By XU Luqing

Few of the Yangtze River’s indigenous species were as well-known as the paddlefish (Psephurus gladius). For thousands of years, the majestic fish delighted travelers on the river, but on July 21, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) declared the 150-million-year-old species extinct, an official confirmation of what conservationists already knew.

In 2019, WEI Qiwei and his team at Yangtze River Fishery Institute suggested that paddlefish might have gone extinct as early as 2005. Wei has been working on paddlefish and other Yangtze species since 1984. By the early 1990s, the population of paddlefish was unable to sustainably reproduce and no longer played a role in the ecosystem.

We talked to Wei Qiwei about the lesson to be learned from the demise of paddlefish and how to help other endangered species in the river.

Jiemian News: How do we decide when a species is extinct?

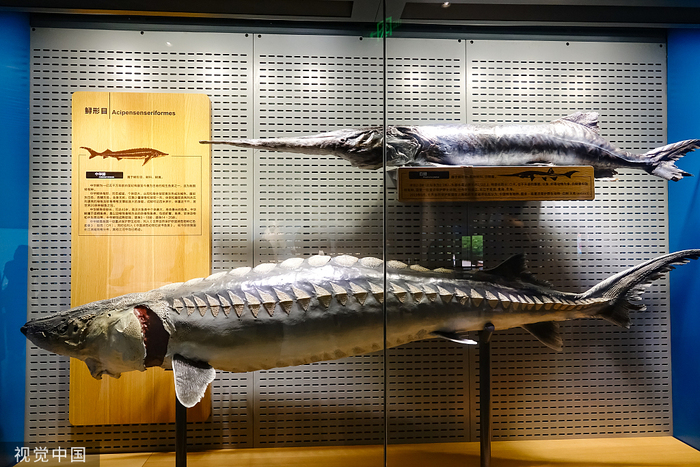

Wei: The IUCN classifies the extinction risk of all species in eight categories. Extinct, the worst-case scenario, means the last known individual has died. In the latest list of threatened species, another fish, Yangtze sturgeon (Acipenser dabryanus) is categorized as extinct in the wild. This means they survive only in cultivation or captivity.

Jiemian News: What drove the paddlefish to extinction?

Wei: Human activity. Noise, overfishing, pollution, and even collisions with ships all harm Yangtze River fish directly. Changes in their habitat, on the other hand, cause harm indirectly. In the case of the paddlefish, they forage near the sea but swim upstream to spawn. Starting with Gezhouba Dam in the late 80s, barriers were erected across the migration route. They are the main culprit.

Jiemian News: You started working in conservation in 1984 and saw your last Chinese paddlefish in 2003. What can you tell us about the population at that time?

Wei: Paddlefish were rare even when I started. In the 80s, their bodies were occasionally found upstream. Some were killed by propellers. Some were caught by local fishermen and died in captivity.

A photo has been circulating on social media of a paddlefish on a riverbank. I took it in 1993. We tried to resuscitate it but it died. In the 90s, we found a few paddlefish that were dying but were not able to save any of them.

The first time we successfully resuscitated one was in December 2002, in Nanjing. It lived for only 29 days, though. Less than two months later, another was found. It recovered quickly and was released into the wild. The plan was to track it all the way to where it lays eggs. But we lost it when our boat ran aground. I didn’t know that I would never see another paddlefish ever again.

It’s harder to resuscitate an adult fish than a juvenile. In hindsight, not nearly enough time and effort was spent on researching juveniles and supporting them. Similarly, we would have preserved paddlefish if there had been captive breeding in the 1960s and 1970s. We are now breeding Yangtze sturgeon in captivity.

Jiemian News: How are sturgeons faring?

Wei: We haven’t seen them reproduce in the wild in the past five years. I worry that they will be gone as well one day. Gezhouba Dam, as well as other hydroelectric projects, have cut off their migration routes. Flood prevention and urban beautification projects destroy riverbeds, where the juveniles hide and grow. Overfishing in the sea threatens adults. Captivity breeding programs help, but they were not efficiently run until recently.

Jiemian News: The government imposed a 10-year fishing ban on the Yangtze in 2020 to conserve wildlife. Do you think it’s enough?

Wei: The ban reduces direct harm, but it is equally important to restore their habitat. The Yangtze connects the most economically active regions of the country. We ship goods on it, generate our electricity from it and dump our waste into it. We harvest sand from the riverbed. We build ports on riverbanks. Even urban light pollution can affect wildlife in the river.

Dams not only cut off migration routes, but they have also completely changed how water temperature fluctuates throughout the year, which in turn affects how fish reproduce and grow. In the stretch near Yichang, for example, winter water temperature is as much as 6 degrees higher than before 2003, when the Three Gorges Dam reservoir was filled. The sturgeon won’t lay eggs in such warm water.

Juveniles often hide and forage near shallow riverbanks. Nowadays many riverbanks are paved so that the waterfront looks “nicer.” There is no food or hiding place on these paving stones. It’s not great for the young fish.

Jiemian News: The Yangtze river is 6,300 kilometers long and runs through many provinces. Conservation requires a great deal of cooperation. What problems do you encounter?

Wei: The Yangtze supports many activities from shipping to agriculture, but regulatory responsibilities are extremely fragmented. Fishing is under the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. HydrDamsare under the Ministry of Water Resources. Water quality is under the environmental authorities. Habit preservation is under the Ministry of Natural Resources. Everyone minds their own turf but there is no mechanism to work together. There is the Yangtze River Protection Law, theoretically, but it is far from enough.

Jiemian News: You once said it is far more difficult to conserve wildlife that lives in rivers and lakes than on land. And in fact, almost all the vertebrates that went extinct since 1949 are aquatic animals. Sturgeon are big and have attracted some attention, but the public has largely failed to relate to smaller fish such as Sichuan taimen (hucho bleekeri). Why do you think that is the case?

Wei: It is more difficult to conserve aquatic animals partly because human activities are intertwined with rivers. We can’t really designate a stretch of water as protected and ban people from entering, as we do on land.

Another problem is public awareness. We don’t see aquatic animals on a daily basis, except in restaurants and food markets. So the public doesn’t usually associate fish with conservation. It’s bad to shoot a sparrow but OK to gut a fish. Fish are dumb and are not as cute, anyway. When land animals are struggling, people can see and empathize. But when it comes to fish, it’s out of sight, out of mind.

Jiemian News: A hydropower station in Sichuan will destroy the river bed where Sichuan taimen lay their eggs. Another proposed dam on Poyang Lake has been widely criticized. Are economic development and conservation incompatible with each other?

Wei: To some extent yes. People won’t prioritize small, innocuous species over hydropower stations, which can bring in huge amounts of money for poor mountain regions. We’ve come to a point where there are too many dams and almost no fish. It’s high time that we reversed that course.

I don’t think we should take down projects that have already been built. But future ones should be closely scrutinized and strictly limited. For a project to be approved, a certain amount of money should be earmarked to remediate its environmental impact, not only in its immediate surroundings but for everyone upstream and downstream.

We need to be more strategic in preserving species. Fishing for 30 percent of Yangtze River species is not tracked or documented. The Chinese paddlefish wouldn’t have gone extinct if we had acted sooner. Granted, it’s hard to restore a species given current technology, but as long as something remains alive, there is hope.