After a lengthy and stressful lockdown, Shanghai is embracing its playful side with a series of offbeat shop signage.

By MA Yue

A month out of lockdown, and Shanghainese still cannot stop talking about groceries. Shoppers who were once sick and tired of carrots and onions – which they had been buying in abundance due to their long shelf lives – are now flocking back to supermarkets to get a look at a whole new genre of quirky product signage right in the heart of the vegetable aisle.

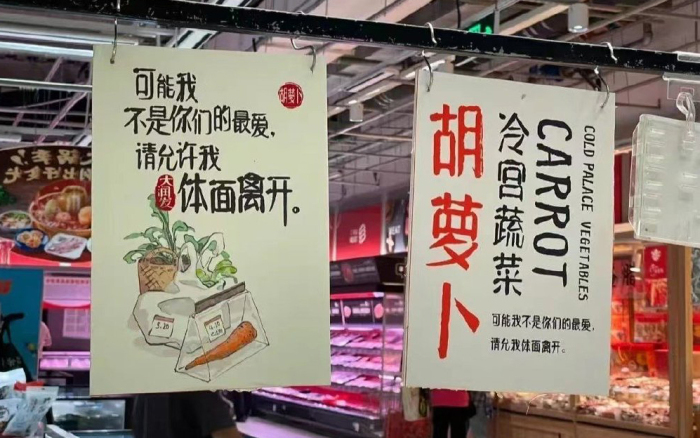

Dubbed “Cold Palace Vegetables,” the delicate signs evoke China’s famed soap-opera scenes where out-of-favor concubines shed tears at being abandoned to drafty imperial palace quarters.

“Let me go if I’m not your love,” one sign says, in goofy handwriting, accompanied by a meticulously drawn watercolor illustration of a wistful carrot.

“We loved,” another says, above a yearning bok choy.

A slew of likes, mentions, and online chatter has seen RT-Mart, the supermarket chain that came up with the cutesy signage, trending on Chinese Twitter-like social media Weibo.

After months of considerable stress and panic, the graceful signs have given the city’s residents something to smile, or even, laugh about, and no doubt Da Run Fa are more than satisfied with the buzz they have caused. Copy-cats have already popped up throughout the city.

Coca-Cola was labeled as a “source of happiness” and “a hard currency,” a tongue-in-cheek reference to a viral meme that called the fizzy drink, scare in lockdown, “happy, fattening, stay-at-home water.”

Garlic and scallions, which many people grew on their balconies to substitute for harder-to-find seasonings or simply to kill time, are lauded as “the light of dishes and fire of meals.”

Grocers quickly adopted the practice elsewhere, from supermarkets to mom-and-pop vegetable stands and beyond.

People and businesses have long understood the power of evocative signs, and Kuaishou, which has been trying to pivot to agricultural e-commerce, recently held a signage show at a farmers’ market in Qingdao to promote existing vendors and encourage more to sign up.

The crossover between groceries and pop culture took off after the pandemic, as newly out-of-lockdown shoppers rushed to embrace the in-person experience they had been denied for so long.

Street fair promoters often cite maicai (buying food from traditional farmers’ markets) and slow food as an antidote against ultra-digitized, overly commercialized modern life. The new signs certainly had a unique, craft feel of a type you would not usually expect in a supermarket chain.

At the same time, online grocers often evoke nostalgia to their own advantage. Sanyuanli Market, a sprawling gourmet food market in Beijing, turbo-charged the movement by hosting a highly publicized, grocery-themed calligraphy show last year. The market, a popular foodie destination, has been hosting art fairs, book releases, and product launches since 2013, in what could be a sign of things to come.