In its prime,150,000 people lived in the informal community of Baishizhou in the heart of Shenzhen, now an urban redevelopment plan is converting the area into yet another collection of anonymous offices and apartment buildings.

A man crossing an alley in Baishizhou on his scooter. All photos by Liang Zhou

By LIANG Zhou

HE Wenwei stood outside a cordoned off area, watching a building being torn down. The sight, which has become more frequent recently, always gives him a bittersweet feeling. His home, Baishizhou, an informal settlement in the heart of Shenzhen, is being torn down, or “redeveloped.”

More than 40,000 people have left the warren since July 2019, most of them migrant workers. On the site, new skyscrapers will arise containing condos, hotels and offices. Some old residents, for lack of alternatives, stayed put for as long as they could, but will eventually move away, too.

The neighborhood is walled off and quiet except for the noise from the nearby Shahe Industrial Area which is also being redeveloped, the tranquility is punctuated only by the occasional explosion as another factory is demolished. People stop for a moment and squint up through the dust toward the sound. When someone pulls out her phone to take photos, a security guard moves her on.

In Baishizhou, as soon as an owner signs the compensation agreement, the building is quickly evacuated and sealed off. The community is a labyrinth of blocked roads and alleys. No one has any idea of how many people still live in Baishizhou. The last estimate was that about 48,000 of the original residents had moved out more than a year ago. Since then, a government statement in January said that “the population has continued to decline.”

Those who choose to remain have their own reasons. He Wenwei has lived there for 27 years and his son attends a local elementary school nearby. Many kids who have moved away remain in their previous schools due to a lack of places in their new neighborhoods. He's family has been constantly on the move since the urban redevelopment project began. When their current building is sealed, they decamp to another, usually even more cramped. They expect to carry out this “guerilla residence” until Baishizhou is completely gone.

ZHANG Xu runs a small restaurant. Her business closed down when her building was scheduled for demolition. But rents elsewhere seemed exorbitant so she came back to Baishizhou and reopened the restaurant albeit on a much smaller scale. Despite being busier than ever, she is making less. “My old customers have moved away. And people don’t have a lot of money to spare this year,” she said. “At least I can still survive here.”

Eagle, 59, owns a tattoo parlor, hidden behind layers of tin walls. A signboard he puts out at the entrance of a nearby alley is frequently removed by security guards. It is almost impossible for anyone to find the place. In August, no one came for more than two weeks. He doesn’t know how much longer his shop will hang on.

LU Liqiang stayed for love. After his divorce, he came to Shenzhen to start anew. He chose Baishizhou because the rents were low and then met his current wife. He works as a delivery worker and can always find the quickest way through the blocked alleys. “I’m not rich, but we are not starving. Maybe this is some divine arrangement. If I had not come to Shenzhen, how would I have met my wife?” Lu said.

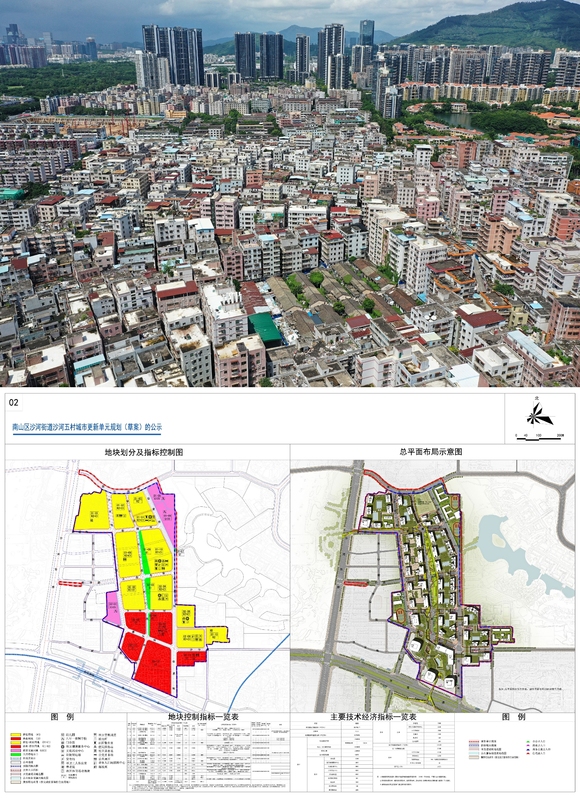

Baishizhou came into being in the late nineties, when migrant workers flooded into Shenzhen’s new “special economic zone.” Dilapidated farmhouses quickly became mid-rise buildings with tight living quarters filled with day laborers or anyone else trying to make a living in the boomtown. In its prime, 150,000 people lived in more than 2500 buildings. Baishizhou is encircled by luxury condos, high-end department stores, and beautiful urban parks. The redevelopment plan first came out in 2005, but until recently, the community had remained largely untouched. Almost a slum, it was the bane of the city’s triumphant urbanization.

Those whose livelihoods are rooted in Baishizhou see themselves as hustlers and dreamers: He Wenwei, Lu Liqiang, and Eagle are all part of this group. In his 30-year career, He Wenwei has worked as a security guard, opened pachinko parlors (not really legal but no one gave him troubles for that), and invested in restaurants. Now he is in the construction business. Two years after his arrival in Shenzhen, Lu borrowed 100,000 yuan to take over the bottled water delivery station he was then working at. Business was good, and he doubled his money in a year. Lu paid off his loan, and invested the rest of the proceeds in a bakery, which thrived as well. Eagle, full of stories of local eccentrics, has supported his family with his tattoo parlor for the past thirteen years.

Urban redevelopment put paid to these ways of life. He Wenwei said 2020 has been his worst year, his investment in a construction project in Hainan is yet to see any return, His wife has to sell breakfasts to make ends meet for the family. He regrets not buying a property in Baishizhou when his construction business was booming—those who did have made a fortune from government compensation.“The city has moved on. We live right in the center of it all but are struggling,” He said.

Lu closed his bakery after learning of the building’s impending demolition. Attached as he is to Shenzhen, he has made peace with the fact that he will eventually leave. He saved some money and bought an apartment in a small northern city last year, where his wife comes from. “You buy a house, and only then can you say you have a home,” he said.

Eagle’s tattoo parlor is obviously doomed, but he plans to hang on as long as possible. His lease is not due up for two years, and more importantly, he doesn’t have anywhere to go. Seeing old acquaintances moving away makes him nostalgic and heavy-hearted. But business picked up recently. “The pandemic is under control,” he said. “And for whatever reason, some people have moved in.”

Demolition, or “urban redevelopment” is the only topic of conversation these days, but Zhang doesn’t care. She likes the place but doesn’t get unhappy over things she cannot control. She occasionally moans to her customers about how cruel things here have become. "Baishizhou was once home to so many people and it kind solved many problems for the city," she said, though no one answered. "Not when they decided you are not part of their planned future, you are gone."

“Baishizhou may look very nice in the future. But thinking about it, it doesn’t really affect me that much,” a previous tenant who moved away earlier this year reflected. She still passes Baishizhou every day on her way to work, but she feels like a stranger to her former neighborhood.

"Life goes on, everyone hustles for his next meal," she said.

The redevelopment project has been progressing well and demolition will start in earnest soon. The impending disappearance of the chengzhongcun – a village that has been swallowed by a city – has drawn more attention than ever from those living outside.

WU Peishi, a high-school teacher, started a photography project with students in the summer, documenting the last days of Baishizhou. Recently, the group held a small exhibition of photos of sanitary workers, street sellers and children of migrant workers. They were shown side-by-side with pictures of Huaqiaocheng, a desirable neighborhood separated from Baishizhou, literally by a wall.

“My parents always told me not to hang out in Baishizhou. They said it was dangerous,” said Chen Hongtao, one of the student photographers, who grew up in Huaqiaocheng. “But when I started looking into Baishizhou, I realized it was pretty typical of big Chinese cities.”

A brochure for the redevelopment speaks of a “new chapter” in Baishizhou’s history, with office buildings and residential high-rises. In this new chapter, the physical and economic border between the two neighborhoods, along with whatever character Baishizhou ever had, will likely disappear.