China’s “shamate” youth were once considered a uniquely Chinese phenomenon. Fifteen years after Luo Fuxing came up with the term, the so-called subculture lives on in the factories of Shenzhen, its history chronicled in millions of selfies.

“The Father of Shamate,” Luo Fuxing. Photo: ZHAI Xingli

By ZHAI Xingli & LIANG Yingxin

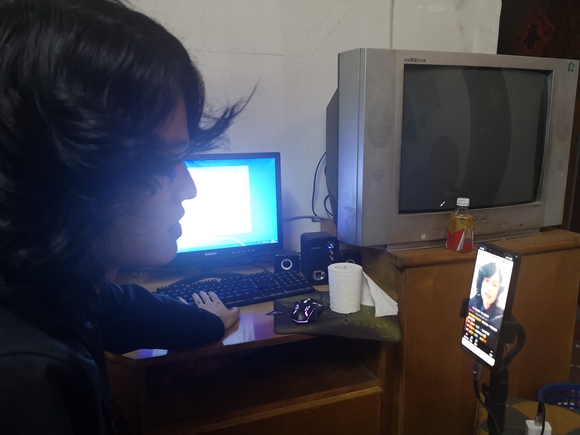

“The Father of Shamate,” LUO Fuxing, is live-streaming when I visit his rental apartment on the neglected fringe of the Dongguan metropolis.

Around 15 years ago, Luo coined the term shamate by sticking together two characters in an ingenious attempt to transliterate that English word “smart,” which he thought was the proper English translation of "fashion." Luo became, or claimed to be, the patriarch of a tribe of young people with exaggerated, cartoonish haircuts: Goths with Chinese characteristics.

“I was the one,” he has told reporters, followers, and detractors countless times. “I was the one who came up with the word shamate.”

Luo was born in Meizhou, a Hakka village in northern Guangdong Province. He dropped out of school almost as soon as he began and spent his days in internet cafes, where one day he surfed up a random picture of Japanese guitarist Miyavi. And Miyavi had great hair!

Luo drenched his hair with lacquer and sculpted it into huge spikes. In a black leather vest, with black fingernails, Luo felt he looked awesome and posted a picture on his Qzone page. At the time Qzone was the nearest thing China had to Facebook and a great many people "liked" Luo’s pic. One comment said, "you look so cool". With happy coincidence and sheer ignorance, shamate was born.

He used it as the name of his QQ chat group, and the rest, as they say, is history. For the next seven years, pictures of pouting teenagers with outrageous hair were all over the internet.

But as American writer William s. Burroughs once said: you can’t eat fame. Luo lopped off his locks years ago and found factory work. He tried to open a hair salon but it quickly failed. Now he’s joined the ranks of the live streamers, hoping to catch some crumbs from a table that is already quite full.

A comment pops up on Luo’s screen: “Shamate is a thing of the past. You and your old gang are just a bunch of fossilized attention whores.”

Luo springs to his keyboard. “Outdated or not, I like shamate for what it was. It was how we expressed ourselves. It was sincere.”

For popular streamers, real-time comments flood the screen. It is almost impossible to pick one and reply. But Luo is not a popular streamer, not by any standards.

It can sometimes be hard to grasp the enormity of live streaming in China. Lou’s Douyin account has less than 200,000 followers: peanuts. Only about a thousand people are watching the stream: next to nobody. The cruel comment lingers on the screen for quite a while as it is slowly engulfed by the dubious wisdom of other trolls, bored at home or in the subway, with their exceedingly normal hair.

“Hey folks, let’s be a bit nicer to each other,” Luo says. It doesn’t help.

Stranded in Chongqing by the coronavirus, Luo only started live streaming this year. He has also made some short videos, typically “The Homecoming of the Shamate Patriarch” – less than 10,000 views.

Luo’s head drops: “I am obsolete, unwanted.”

Rampaging self-esteem was never the hallmark of shamate, but even so, things might not be as bad as they seem. As it transpires, short video platforms like Kwai don’t like the word shamate and the system automatically blocks it. When Luo uploaded videos on hairstyling and avoids mentioning shamate, to his surprise, the videos received many more clicks.

“Don’t fight the system,” he sighed. “The platform system is no different from an assembly line. They tame you. You keep them happy or you starve.”

Being a good little streamer gets Luo more clicks, but clicks are all he gets for now. On November 8, after a long night of live streaming, after the streaming platform took its 50 percent, he pocketed 12.5 yuan (US$2).

“The river flows by my window,” Luo joked. “The Fengshui here is very good.”

Luo’s apartment costs 600 yuan a month. The building is in an alley with no name or streetlights, beside a fetid stream. Two stinking dumpsters mark the entrance. He found the place by going door-to-door to avoid paying a real estate agent. The two rooms seem almost spacious with just a wooden sofa, a tea table and an old computer. The computer is basically a music player when Luo is on air. Music makes the atmosphere less awkward.

He sits on the sofa with his phone propped up on the tea table. The sessions are boring. Viewers ask pointless questions. What have you been up to recently? Is that betel nut you are chewing?

But Luo is a deep thinker, a sociologist with Gustave Le Bon’s The Crowd and James Scott’s Weapons of the Weak on the tea table beside the phone. He got the books from reporters and academics who sometimes visited him. And he has read them: “A reporter told me shamate was a kind of resistance, and I think he had a very good point.”

He tried to talk to his dwindling shamate family about resistance: “They couldn’t care less. They are migrant workers. All they care about is money and fun.”

Indeed, for the few young shamate, it is just fun. They think exactly like Luo did when he first sculpted horns onto his head all those years ago.

“We are normal people who love the shamate hairstyle,” said Little Shamate Princess, a 21-year-old girl who works in a factory. “People look at me like I'm a superstar. It feels good to be a superstar.”

Like Luo, Little Princess quit school at a young age and came to the city. She has big hair and big dreams. She’s going to make a movie about the tribe. But she has no idea about a script, financing, actors, or equipment.

Luo met Hongshao and Xiaobai online. Both born in 2000, they came to Shenzhen in 2014. They take jobs when they find them, save some money, give up their jobs and when the money is gone, return to the assembly line.

This is shamate, the next generation, and they don't care about making a social statement or organizing themselves into a movement. But they have a lot in common with the Luo 14 years ago: they are migrant workers who refuse to suffocate in the boredom and depression of life in the factories.

In 2018, before short video platforms banned it, the “Shamate Renaissance” became a meme that spawned shamate emojis with funny captions. There is no doubt that attention-seeking was an important part of the subculture, so Luo and his cohorts thought they were making a comeback. Well, they weren’t. Surely Luo wouldn't be able to figure out the mockery and venom of the memes until they eagerly took to the internet. Humiliation awaited.

“There was never a revival,” said Luo. “It was just people making fun of us, as they did ten years ago.”

In 2018, LI Yifan started to make the documentary We Were Smart. At the time, he believed there was more to shamate than just whacky hair. Li was a lecture at Sichuan Fine Arts Institute who told his students that China finally had a proper punk culture, but by then, Luo and most of the tribe had cut their hair and were back on the assembly line.

“They were endowed with ideas they didn’t even know about or were interested in,” Li said. “They had no notion that they were swimming against a tide of popular opinion. They expressed themselves freely without ever thinking about freedom of expression. They were just a group of marginalized young people, cuddling up together because they were lost and lonely. There was nothing sophisticated about them at all.”

When making the documentary, Li asked Luo to get his old gang back together. Excited as they were when they heard about the project, few showed up.

AN Wenxuan cut his hair and joined the army in 2013. He is now a field survival expert and a rescuer. His team calls him “crocodile” for his bravery. An kept in touch with some of his shamate “family,” but they don’t talk much about hair or make-up these days. Now it’s work, marriage and kids. An sees no sign of a so-called revival of the subculture. “I worry about the kids now,” he said. “I worry that they may do stuff in the name of shamate that brings shame to their families.”

When asked why he didn’t want to meet Luo and Li, An said his iconic hair was long gone and unlikely to return, so there was is no point in going. “Soldiering is more important than shamate,” he said. “Though it would be good to make a movie about it one day if I ever get rich.”

Despite the lukewarm reception from dispirited youth, Li decided to make the documentary anyway and began in Shenzhen. Even with the help of Luo, it was difficult. The two reached out to some 700 shamate, and only 67 agreed to appear on camera. Most thought it was just another mean joke.

Li found the shamate all had some things in common. Born after 1990, they had all dropped out of school very young. They worked in factories for pathetically meager wages and lived for the day.

Reality began to bite when Li and his team met Bai Feifei, a shamate girl who had been working in factories for years. Shenzhen’s industrial sprawl is huge and Bai worked in a very remote factory. The feasting and revelry of metropolitan Shenzhen were as far off as Paris or New York. She had spent years watching the lights of the coastal city from afar. Bai’s dream was to have a glimpse of the sea, 50 km away.

To observe the shamate in what he supposed was their “natural habitat,” Li rented an apartment close to where Luo lived. He was disappointed. Every night around 9pm when they finished work, they would meet up to eat, talk, and maybe wire some money back home. Nothing interesting happened at all. The eccentric, unreasonable youth portrayed online was just a bunch of low-key mates hanging out together in real life.

“I did not meet one single shamate with something to say,” Li said. “They were all as bland as the next man on the assembly line.”

Li moved among them for more than a month, assailed by unsolved mysteries. Did shamate even know whether or why the mainstream disliked them? The answer was almost absurd. Trapped in their migrant worker bubbles, they only really communicated with their buddies, one was as poorly educated as another. They didn’t even know there was a mainstream, let alone what it was and why it despised them. They just thought they were the coolest guys around.

The boys talked only about work and girls. Li would have been surprised if the girls were much different. In their selfies, their gesture of choice was “Finger Heart.”

“They didn’t even have complicated concepts such as resistance or rebellion,” said Li. “They were just a bunch of left-out kids, who snuggled up together for care and warmth.”

Luo does his math. An average worker in a Dongguan factory earns 3,000 to 3,500 yuan per month. A tiny apartment in the urban fringe of Dongguan costs at least 360,000 yuan. He has to save 3,000 yuan every month for ten years if the housing price stands still.

Luo wants a home. He’s heard of lots of people getting rich through live streaming, though all platforms seem to be mean. “Netizens shouldn’t troll us,” he says, and he’s right. But still, they troll. “I have no choice but to put up with their nasty words. Their problem is what to have for supper. My problem is whether I have anything to eat.”

During the National Day holiday, Luo wanted to hang out with some of his old shamate friends, but the police arrived before his friends and called the party off. They were even quite nice about it.

“You know, a lot of people don’t like your thing much. You and your friends are not well-educated,” the officer told Luo. “I’m telling you this for your own good.” And he probably meant it.

This sent Luo back to the old days, walking around in Shenzhen with his big hair when two policemen took him to the station and made him take a urine test. One of them looked at Luo’s ID card and saw he was a fellow Hakka. “You are a disgrace to our people,” the officer said.

Luo's father passed away four years ago. His mother is in Shenzhen, working around the clock to feed his two younger sisters. Luo wants to buy his mom a home. The stories he tells about himself have changed over the years and he reckons he has learned a little about the boundary between daily life and daydreams.

“It doesn’t matter if I was the one who came up with shamate. It didn’t thrive or die out because of me,” he said. “And it won’t have much to do with me whether it fades away or comes back to life. What’s done is done. I’ll always be a shamate.”

Luo is uncomfortable with live-streaming and making videos, but he’s out of ideas. It’s that or the assembly line, but the assembly line is not as easy as it used to be. He’s thinking about going home to Meizhou. At 25, Luo has been a migrant worker for 12 years, but he’s made plans for his return.

“I’ll start out by breeding pigs. When I make some money with the pigs, I’ll get some cows,” he said. “Then, I’ll have fishponds. Finally, I’ll buy a motorbike and patrol my ranches.”