One of Shanghai’s best-loved second-hand book sellers has been forced to start spreading his love of books online.

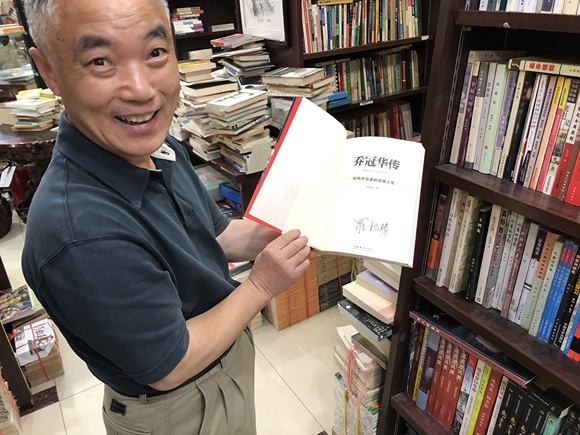

Zhu Fengtao standing among shelves and piles of books in his second-hand bookstore Little Zhu's. All

By YANG Shuhongji

For years, Little Zhu’s Bookstore in a community center near Lujiazui has been the chosen stomping ground of local bibliophiles.

The little second-hand store, no bigger than a normal apartment, is home to eighty thousand books, meticulously categorized and displayed. Another three hundred thousand are hidden in storerooms nearby.

There is no typical customer at Zhu’s. Scholars come hunting rare old books. Passers-by seek traces of old Shanghai.

Little Zhu himself once defiantly resisted social media, but now keeps busy trading used books online and hosting virtual book clubs. He tries to reply to every inquiry, many of which have nothing to do with books at all but are more concerned about the store’s survival.

The book trade is a Zhu family tradition. Little Zhu’s father peddled books on the streets, until he was hired by a state-owned bookstore and, in 1979, Little Zhu, then twenty-one years old, became a junior store clerk at his father’s branch on Sichuan Road, a busy street at that time.

In the 1990s, as private enterprises began to take off, Zhu opened the first subway station bookstore in Shanghai. His business thrived for a while but wasn’t able to weather the onslaught of e-books and e-commerce, so he closed down his locations and rented a small space in the Metro station near his home and started selling used books. Word quickly spread on the quality of his collection, and Little Zhu’s became the go-to place to prospect for second-hand literary gems.

So popular was the store that, when it was threatened with closure due to rising rent, the municipal government, keen to preserve local landmarks, helped the store negotiate a friendly lease and relocate.

Customers are awestruck by the sheer size of Little Zhu’s collection — there is something on almost every genre or topic, from serious literature to comic books, from China’s modern diplomatic history to Soviet economics.

Once an elderly woman came looking for a knitting magazine she saw decades ago and only vaguely remembered the cover, not even the date. When Zhu dug it out from a nondescript stack of old magazines, she was more than delighted. “There it is! Yes, I still remember these illustrations!”

Zhu revels in moments when readers are reunited with their old loves after a long separation. “A book is key. In the hands of its destined owner, it opens the door to memories,” he said.

Even reading notes left by previous owners on the margins can be seen as a conversation across time. “Trading books is like taking care of other people’s lives. It’s a people business. I collect everything that comes my way.”

When a businessman called from Fujian to trade in a complete set of “Anthology,” a four-thousand-volume collection published over a thousand years, he asked for 200,000 yuan (US$28,500). There was no way Zhu could afford the collection, but he still went to Fujian to have a look. “It could be the best-preserved set in the entire world,” Zhu explained.

The collection once belonged to the seller’s grandfather, who, during the Sino Japanese War, kept the four thousand volumes with him during the evacuation of Shanghai, carrying them almost 1,000 kilometers to Fujian where he found work at a teachers college. Zhu decided it was a worthwhile purchase, even if he didn’t end up reselling it, because, “the history behind it is priceless.”

As a bookseller, Zhu appreciates the true value of books rather than the mere monetary. Every year he donates hundreds of books to rural areas. He hosts book fairs and runs a kind of ad hoc local lending library. “We give away so many used books every year. It makes me happy to get the right books to the right people.”

Zhu considers himself an old-fashioned businessman. He refuses to add a cafe to his store and resisted selling books online until the epidemic struck. His customers love the sense of hunting for treasure at Little Zhu’s. One of them, Qiu, owns more than thirty thousand books himself, and has been visiting Little Zhu’s “for ages.” For him, the store’s biggest appeal is to be able to sit down in a corner and start reading immediately. “Old books are particularly enjoyable. They are edited with a rigor that’s rarely seen in contemporary times,” he said. As an old friend, Zhu allowed him in to the store during lockdown to find a few books for his granddaughter.

The epidemic forced many businesses to find a way out online, but Zhu initially refused to do do. The community center waived his rent, but customers continued to bring in old books and the overloaded inventory pushed up storage costs.

As many bookstores go under, Zhu finally allowed his son to convince him to start an online business. He put up a notice on the storefront, instructing booksellers and customers to drop off and pick up books “contactless.”

Zhu has been reorganizing his shelves. He emptied two entire rows for a Shanghai art and literature history collection. After all, his bookstore is a small landmark in Shanghai’s cultural history itself, exactly as Zhu likes it.