Xilingol League is an active focus of Mongolian gerbil plague. Here plague among rats has been often year in year out. A man ate a wild rabbit and was later diagnosed with bubonic plague.

Photograph: CHEN Xin

By CHEN Xin

The wild rabbit appeared in the boiler room out of nowhere. At the sight of it, LIU Qingxi, 55, Henan Province, put down his work.

Liu Qingxi was working at Jiabusi Niobium-Tantalum Mine of Mengjin Mining Corporation in Xianghuang Banner (Xianghuangqi), an administrative subdivision with a population of 33,000, in the Southwest of Xilingol League, Inner Mongolia.

Xianghuang Banner gets drier year after year. It was not until Nov. 5 that the first snowfall in 2019 encrusted the mine and its surroundings in glistening white flakes.

Liu caught the wild rabbit, filleted it, and shared it with three coworkers.

Eleven days later, after days of recurring fever and ineffective cold medicine, Liu travelled dozens of kilometers away for further treatment in Huade County Hospital, where he was diagnosed with bubonic plague.

The plague is more formally known as Yersinia pestis, a highly-infectious disease which is transmitted easily through animals bitten by fleas. Bubonic plague, if it worsens to pneumonic plague, can spread through droplets and air, which may lead to a massive outbreak.

Two hours after Liu received his diagnosis, Huade County Hospital reported the case to the municipal-level health bureau. The 20 medical workers who gave Liu his initial diagnosis, including the hospital’s vice president, were quarantined.

Word of the plague case spread rapidly throughout Xianghuang Banner. Eight more close contacts were quarantined on the site of the mine. Mine staff took shifts to seal off the location, and the local government delivered food.

At noon Nov. 23, the pain in Liu’s left armpit abated. The electrocardiogram indicated no abnormality. The consulting experts advised continuous active treatment based on his generally stable condition. The 28 people who came into close contact with Liu were permitted to leave quarantine.

In the days following Nov. 16, people going to and from Xianghuang Banner and Huade county planned for longer travel time. Several police officers linked up alongside the road. They stopped each and every passenger to register, and to get their temperature taken.

Soon Beijing Chaoyang Hospital confirmed two patients from Sonid Left Banner, Xilingol League with pneumonic plague. On Nov. 12, Inner Mongolia took action to prevent and control the spread of the plague. The prevention measures escalated as the Health Commission of Inner Mongolia reported the treatment of another infected patient from Xianghuang Banner in Huade County Hospital.

The head of the Publicity Bureau of Xianghuang Banner told Jiemian News that after the plague was confirmed, experts from Xilingol League, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) all came to the concerned area. “On the very second day after the diagnosis of plague, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) experts in epidemic prevention came out to train and educate hundreds of local officials and healthcare staff working in the four towns and pastoral areas.”

Doctors from Bayantal Township Hospital worked around the clock in three shifts at roadside checkpoints. Nurses eventually lost count of how many times they sterilized the hospital’s gate areas. Although still 30 kilometers away from the niobium-tantalum mine, the town lies on the only road leading to the mine.

To local herdsmen, the plague incident happened because of the workers’ lack of knowledge of local way of living. “People never get infected as long as they don’t touch or eat wild animals,” villagers explained, “Otherwise, we would have already been infected.”

Nearly half a century ago, the region suffered an extended outbreak of the plague 41 of the years between 1901 and 1949. It affected 9 leagues or cities in Inner Mongolia. 80,000 people died. Very few who caught the disease survived.

Xilingol League, where the recent outbreak occurred, has suffered the plague four times since the founding of People’s Republic of China. The last occurrence was 15 years ago. On Nov. 5, 2004, one herdsman of Sonid Right Banner was treated by community physicians with a suspected case of the plague. He had eaten an infected rabbit.

As explained to Jiemian News by a researcher of the Inner Mongolia Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau, rats suffer plague epidemics approximately every ten years. “The autonomous government has attached great importance to this event. The whole region is terminating rats. There should be no big problem as long as people stick to the ‘3 Don’ts and 3 Reports’ as advised,” (Three don’ts refers to: don’t poach, don’t skin, don’t eat animals with the plague. Three reports refers to: report sick or dead rats and animals, report suspected plague victims, report high fevers of unknown origin and sudden deaths.)

On Nov. 17, the second day after the plague was diagnosed, about 300 officials and workers, wearing white protective suits, masks and gloves, began an extermination campaign for rats and fleas within a 1.5 kilometer radius around the boiler room in the niobium-tantalum mine. On Nov. 21, the local government mobilized another 100 or so persons to further exterminate rats and fleas.

LIU Qiyong, chief scientist in vector organisms of CDC, told Jiemian News that it’s important that both rats and fleas are eradicated in a plague area, “otherwise after rats die, fleas will look for new hosts, even human hosts,” he said. “If that happens, there’s an increased risk that humans will be bitten by fleas and will catch Yersinia pestis.”

According to Xianghuang Banner’s publicized news, planes will complete the eradication campaign on Nov. 22. By then, a total area of 200,000 mu (133.33 square kms) would be disinfected. Local herdsmen grumbled to Jiemian News that they won’t be able to graze their herds for a while due to the toxic rodenticide sprayed over the pastureland. Sheep would be kept in a limited vicinity around their houses and fed on fodder in stock.

“For township hospitals, what’s important is clinical diagnosis. In the event of discovering suspected symptoms, doctors shall refer the concerned case to superior hospitals and report relevant samples to local disease prevention and control center.” Said Liu Qiyong of CDC.

In Inner Mongolia, natural foci of plague spread across 57 banners and counties, covering an area of up to 337,000 square kms. Huade and Xianghuang became new natural foci of plague among animals in 1991.

LIU Shurun, a well-known grassland ecologist and professor of ecology at Inner Mongolia University, spoke to Jiemian News. He raised the possibility that contagion is low when there is rat scarcity but that, if the quantity of rats reaches a certain level, the odds increase that Yersinia pestis makes inroads on other rodents and human beings.

“Plague among rats is common, but it’s exceptional that humans are infected.” Liu Shurun pointed out. “Control and treatment are relatively easier in the beginning phase of bubonic plague. Once the plague spreads out, casualty is extremely high.”

A doctor of Huade County Hospital told Jiemian News that “Once the two plague patients from Xilingol were diagnosed in Beijing, our hospital raised our alarm for patients from nearby pastoral areas. Knowing that this cold-catching patient is from Xilingol, we decided to carry out special inspections. He was quarantined immediately after being diagnosed as a plague patient.”

Liu Qiyong thought that it’s ideal that humans be completely insulated from plague animals, considering the vast area of plague foci in Inner Mongolia. “The risk still exists.”

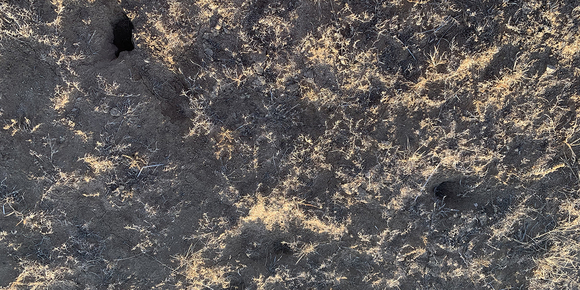

The temperature fell to minus 10℃ in Xilingol in late November. But the prairie is yet to be blanketed by winter snow.

As far as the prairie stretches in sight, plants are less than 10 centimeters high. Grass patches sprawl and scatter on this semi-arid grassland interspersed with rat holes everywhere.

Local residents say winters are getting warmer and warmer. “Snow falls later and later year after year,” said Liu.

“The presence of plague is somewhat correlated with climate change, which causes abnormalities of epidemics, i.e. premature or delayed outbreak in certain years and seasons,” explained Liu Qiyong. “Theoretically, bacteria and their medium, fleas, are less active in low temperature, along with the restricted movement and dormancy of their host animals, reduce the risk of epidemic diseases.”

In a press conference on Oct. 30, the Inner Mongolia Weather Bureau introduced that average temperature of the first three quarters of 2019 was the fourth highest since 1961. Average temperature of Xilingol League was 1 to 2.4 ℃ higher. What’s worse was that the middle part of Xilingol recorded a precipitation 20% to 50% lower than the average amount in the same period from 1981 to 2010. Most areas saw a medium level or higher drought.

When asked about whether local grassland ecology is conducive to rats’ proliferation, ecologist Liu Shurun was unequivocal. “Yes,” he said, three times. “Located in the southern part, Xianghuang Banner is better developed and more populous. Its smaller pasturelands provide for more livestock and subsequently degrade harsher than northern grasslands.”

The 81-year old professor is concerned by the grassland’s ecology. “Even if it rains, the uncovered earth left by degradation does not preserve water. Rainfall soon evaporates.”

An ever-drier grassland in the process of desertification turns out to be most favorable for Mongolian gerbils. “A deteriorating ecological environment compounded with peak numbers of rats leads to plague endemic.” warned Liu Shurun.

Most locals think the prairie’s ecology has been recovering well. This and the ban on hunting, have led to increased numbers of rats and wild rabbits.

WU Xiaodong, professor of College of Grassland, Resources and environment, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, once told Jiemian News that, “A survey in this Spring shows that the threat of rats is significantly higher in Xilingol. On average, there are more than 1,000 rat holes per hectare. Some heavily inflicted areas have more than 1,500 rat holes per hectare.” (1,000 valid rat holes per hectare is rated extreme risks.)

A paper published by MAOWU Liji of Xilingol Center for Endemic Disease Control in April, 2017 pointed out that for many years, Xilingol League is an active focus of Mongolian gerbil plague. Here plague among rats has been often year in year out. Records show positive plague evidences in 7 out of every 10 years.

(LIU Qingxi is an alias.)